One day in May 2010, Laszlo Hanyecz, a 28-year-old Hungarian-born software programmer, exchanged 10,000 bitcoins for the delivery of two large Papa John’s pizzas. The coins, given bitcoin’s value at the time, cost him $41.

Hanyecz wanted to demonstrate that bitcoin, a form of digitized money that was only a year old, could be used in the real world, for routine transactions. Unlike traditional currencies, bitcoin enabled users to make payments under a pseudonym, without the involvement of a central bank – a feature that money launderers, drug traffickers, and online scammers were quick to take advantage of. But it remained uncertain whether cryptocurrencies could live up to their promise as currencies, achieving the same stability and ubiquity as government-backed money.

Papa John’s delivered Hanyecz’s pizzas. But 11 years later, with bitcoin hovering above $32,800, the programmer’s order proves the exact opposite point that he was trying to make. If Hanyecz spent the same number of bitcoins on pizza today, it would cost him $328 million. Bitcoin has turned out to be far too volatile to serve as a reliable medium of exchange.

Papa John’s Pizza

Nowadays, almost no one touts bitcoin and other decentralized, peer-to-peer cryptocurrencies as a way to buy your groceries or pay your mortgage. Enthusiasts pitch them as a potentially lucrative investment, a hedge against inflation, and a tool for evading government surveillance.

But there is one form of cryptocurrency that is still angling to replace the credit cards and cash in your wallet. Stablecoins, which peg their price to physical assets outside the cryptocurrency space, aim to combine the best of both worlds. Like traditional cryptocurrencies, they enable users to make transactions quickly, cheaply, and privately. But like regular money, their value is fixed to currencies such as the dollar, or to commodities such as gold. That means they aren’t susceptible to the wild price swings that have plagued bitcoin. And they can be redeemed at any point for their backing assets, which makes them feel safer and more trustworthy.

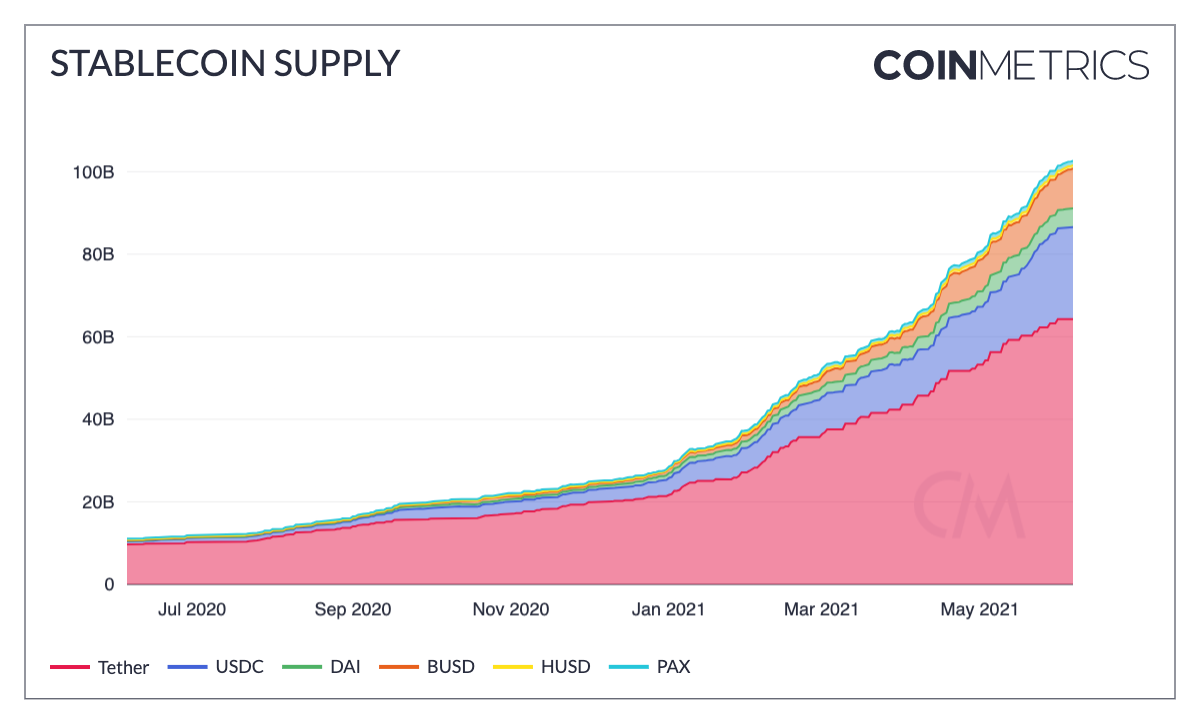

The result has been what some observers are calling a “stablecoin invasion.” Tether, which maintains a one-to-one peg against the US dollar, is now the third-largest cryptocurrency, right behind bitcoin and ethereum. According to a recent report, there are now at least 200 stablecoins in the market or under development, including USD Coin (USDC), Binance USD (BUSD), Dai (DAI), TrueUSD (TUSD), and Paxos Standard (PAX). In the first five months of this year alone, the supply of stablecoins pegged to the dollar more than tripled, to $100 billion. “The pace of growth has been just astonishing,” said Nic Carter, a founding partner at Castle Island Ventures.

Coin Metrics

At the moment, stablecoins are mainly used within the crypto ecosystem, in much the same way dollars are used in traditional financial markets. Venture-capital firms like Castle Island use stablecoins to fund their investments in startups. Crypto traders keep a ready supply on hand for fast transactions and accessible collateral. And a growing number of investors are parking stablecoins in crypto savings accounts, which offer yields as high as 10%.

But many experts predict that in the next three to six years stablecoins will serve as a major currency for transactions between consumers and merchants. “If some of the most popular digital wallets in the world, like Alipay and Venmo, start thinking about stablecoins as a serious way of payment, then it’s going to become much more commonplace,” Kinjal Shah, a senior associate at Blockchain Capital, told me. “I imagine a world where people will be earning digital assets, they’ll be spending digital assets, they’ll be investing in digital assets. Stablecoins will become much more predominant, rather than going back to a bank account.”

A ‘key piece of plumbing’

There are three groups of users driving the current explosion in stablecoins. The first is the crypto industry itself, which, ironically, keeps its track of its own funds in stablecoins. Since January, the total market capitalization of cryptocurrencies has soared to a peak of $2.56 trillion from $772 billion, creating a huge internal demand for a reliable digital currency. “Stablecoin growth partly reflects the growth in crypto-firm balance sheets,” Carter, the venture capitalist, said. Because of the pivotal role they play, stablecoins are often described as a “key piece of plumbing” in crypto markets.

The second group that relies heavily on stablecoins is made up of venture capitalists and traders, who are always searching for more efficient ways to move money between exchanges around the world. “If you’re sending wires, you can only do it from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. five days a week,” said Peter Johnson, a partner at Jump Capital, the venture-capital affiliate of proprietary trading firm Jump Trading. “That doesn’t work when you’re a global trading business and you need to be able to move money 24/7, quickly and cheaply. That’s what stablecoins allow you to do.”

Private investors make up the third group. They’re depositing stablecoins in bank-like crypto platforms such as BlockFi and Voyager, which offer significantly higher interest rates than traditional savings accounts. The deposits are not FDIC-insured, like funds saved in traditional bank accounts, but the rates are so eye-popping that investors are willing to take the risk. “A lot of people see those yields and they say, ‘Maybe I don’t even care about the crypto, but I’m going to hold stablecoins because I can earn this 10% yield on them,'” Johnson said. “That is going to be the entry point. Once you get millions of people holding stablecoins because of the yields, now you just need to convince them to start spending those stablecoins.”

Some stablecoins are backed by other cryptocurrencies, or even by algorithms. But the most common and popular versions are backed by the US dollar or the euro. There are more than 62 billion tether coins in circulation, for example, which means over $62 billion is supposed to be held in reserve to ensure that the coins are fully backed and liquid.

The financial reliability of dollar-backed stablecoins is already getting a real-world test in countries where local currencies have been rendered worthless by hyperinflation. That’s especially true in Venezuela, where decades of rampant mismanagement and corruption have fueled one of the worst hyperinflations in history. As of April, annual inflation in Venezuela was running as high as 2,941%, driving down the minimum wage to just $3.30 a month. Five pounds of chicken that cost 14 million bolivars in 2018 would still cost almost 7 million bolivars today, even after government-initiated curbs on inflation.

Carlos Garcia Rawlins/Reuters

Under these circumstances, the bolivar has become known as the “ice cube” for the rapid speed at which it loses most of its value if not converted quickly enough. “In Venezuela, nobody wants to hold bolivars,” Simon Chamorro, the cofounder and chief executive of a crypto payments company called Valiu, told me. “As soon as people get paid, right away their main objective is to convert it to cash dollars.” The problem is that the US currency circulating in Venezuela is mostly in 20s and 50s, which isn’t very useful when a single dollar is worth over 3 million bolivars. In addition, there is no way to safely store dollars at Venezuelan banks, and Venezuelans can’t access dollars via a US bank account or Zelle without a passport, a visa, and the necessary documents for account approval. “It’s just a very inefficient system,” Chamorro said.

That’s where dollar-backed stablecoins come in. Chamorro’s company has built a mobile app that allows Venezuelans to hold a balance in stablecoins, which can be converted to bolivars, and vice versa. “The interesting part is in a low-trust society like Venezuela, people don’t even care about the fact that they’re crypto,” Chamorro said. “People care about whether they can trust in this company that is providing the solution.” By using stablecoins, he added, the app gives people access to “money that has value and that is being traded on exchanges.”

The stablecoin tug of war

Chamorro’s app points to a future in which digitized currencies like stablecoins are as ubiquitous and accessible as government-issued money. But before that can happen, stablecoins must establish the most important element for any currency: trust.

Stablecoins essentially represent an unregulated form of private money – and right now, the companies behind stablecoins can pretty much do whatever they want. Lael Brainard, a governor on the Federal Reserve Board, recently compared stablecoins to the private paper banknotes that proliferated during the wildcat banking era of the 19th century, which she said was “notorious for inefficiency, fraud, and instability in the payments system.” Indeed, it was the unreliable and often criminal nature of decentralized, private currencies before the Civil War that led to the creation of a uniform national system of government-backed money.

In a crypto ecosystem ruled only by caveat emptor, there are already plenty of warning signs that stablecoins aren’t entirely trustworthy. In February, the Hong Kong-based parent company of Tether was fined $18.5 million by New York regulators for misleading investors about the degree to which its coins were backed by US dollars. And in June 2019, after Facebook announced plans to create a stablecoin called Libra that would be pegged against a basket of currencies, the company received so much regulatory blowback that it was forced to delay the coin’s launch, change its name to Diem, and move the entire project to Switzerland, which is known as the “crypto valley” for its lax approach to regulation.

Erin Scott/Reuters

“Unlike central bank fiat currencies, stablecoins do not have legal tender status,” Brainard observed. “Depending on underlying arrangements, some may expose consumers and businesses to risk. A predominance of private monies may introduce consumer protection and financial stability risks because of their potential volatility and the risk of run-like behavior.”

To Caitlin Long, the founder and chief executive of Avanti Bank, Brainard’s comments telegraph that the Fed, which so far has taken a hands-off approach toward stablecoins, will eventually begin to regulate them. “That should not be a shock to anyone,” she told me, “because anything that touches the US dollar ultimately touches the Federal Reserve directly or indirectly.”

Carter, the venture capitalist who makes his startup investments with stablecoins, expects to see “a tug of war” when the regulators finally take action. “In the US, a lot of policymakers don’t love that payments are being cleared outside of the existing dollar system,” he said. “So they’re going to try and claim the stablecoins into that regulated banking context, whether that means forcing them to get bank charters or trying to regulate them out of existence.”

But a growing number of crypto bankers are beginning to embrace regulation, which they see as essential to making stablecoins truly stable. Avanti Bank has received a charter from the Wyoming State Banking Board, which will make it easier and less risky for customers to cash in their digital assets for US dollars. In May, Diem announced that it would return to the US from Switzerland and subject itself to US regulations before its launch later this year.

Other stablecoins have gone even further. Circle, the builder and backer of USDC, the second-largest stablecoin, is attempting to brand itself as a regulated alternative to Tether. USDC, which has a BitLicense in New York, is also regulated by the federal Financial Crimes Enforcement Network and audited by Grant Thornton, a third-party global auditing firm.

“As a company, we’ve always been building around regulation – inside the perimeter of the regulators, as opposed to outside of it,” said Dante Disparte, the chief strategy officer and head of global policy for Circle. Disparte came to embrace regulation after serving as one of the top executives on the protracted Diem launch. “To be able to back the concept of trust in a digital asset,” he said, “you have to have a high level of transparency around that.”

Money and trust in the digital future

Money – the proposition that a piece of paper, or a series of ones and zeroes, has a fixed value that everyone agrees on – is inherently weird. What makes a currency work, ultimately, is whether people believe in it. “Trust is an important piece of the solution,” said Alex Kern, an intelligence analyst at CB Insights. “Users need to trust the issuer that they have the reserves, and you need to have them regulated so that you can trust them. That means it becomes part of the standard regulatory financial structure that crypto was trying to be separate from.”

Bitcoin maximalists might not like this deviation from the original vision of cryptocurrencies, which were created in large part to evade oversight by the state. But many say it’s a trade-off they are willing to make in order for stablecoins to achieve mass adoption. To pave the way for a stablecoin future, a company called First Digital has already built the payment rails and platform that merchants will need to accept, hold, and convert Diem coins once they launch.

“When will 100 million people use stablecoins?” said Ran Goldi, the founder and chief executive of First Digital. “That will take, surprisingly, only about two to three years. Because we cannot underestimate the power of Facebook, PayPal, Visa, Google, and Amazon – and each one of those players is now making moves” to accept payments in stablecoins.

In the long run, stablecoins issued by for-profit companies may eventually go the way of private currencies from earlier eras. Just as the government stepped in to create a national system of money after the Civil War, Fed Chair Jerome Powell recently announced that the Fed was thinking about creating its own stablecoin. Known as central-bank digital currencies, the CBDCs would be designed for use by the public – a move that could spur millions of consumers and merchants to conduct their daily transactions in stablecoins.

And it’s not just the Fed. The Chinese central bank, which started working on its own CBDC in 2014, has been handing out millions of digital yuan to citizens as part of a trial project, and the Bank of England is looking into launching its own digital pound, or “Britcoin.” All told, according to a survey by the Bank of International Settlements, nearly 50 central banks, which represent 91% of the world’s economic output, are at various stages of developing their own CBDCs.

As central banks mint their own digital money, the companies behind private stablecoins may be reduced to providing the technology and infrastructure for the centralized currencies. Diem, for example, has said it will phase out its stablecoin if the Fed launches a CBDC. “Stablecoins are a patch between now until the time that every country in the world will advance to digital forms of payment,” Goldi of First Digital said.

Ultimately, though, it may not matter what kind of stablecoins we are paying with, but how we are paying for things. “Over time, it all becomes invisible to the consumer,” Kern of CB Insights said. “They know they’re paying with a stablecoin, but they don’t understand that, or it doesn’t matter to them. They’re just paying with an option that they find easiest for them. The ultimate goal is that everything gets abstracted away, and you’re paying with your phone.”